Neurotypicality is as simple as stairs.

“Yeah, but isn’t everybody neurodivergent?”

It’s one of the most common questions heard in conversations about ADHD. Sometimes dismissively, and sometimes well-meaning, the reasoning goes something like this: If everybody has trouble with executive function sometimes, then doesn’t that mean that everybody’s a little bit ADHD?

If it’s dismissive, it’s usually trying to avoid or ignore some kind of accommodation that has been requested or given. You don’t really need or deserve special treatment, the reasoning goes.

If it’s well-meaning, it’s usually intended as comfort. You aren’t really different than the rest of us, they want to imply. Why separate people into categories that are fuzzy at best? It’s an empathetic We’re all in this together,and I personally appreciate the effort.

It doesn’t help.

I can prove that neurodivergence — and neurotypicality — exist.

Because I understand knees. In particular, I understand my bad knees.

The Bad Knees Analogy for Neurotypicality

Let’s agree that most humans, barring a genetic anomaly or physical trauma, have knees.

I’m not a medical expert* but given the number of factors involved in the knee-joint mechanism (cartilage, bone, tendons, ligaments) I suspect they’re a lot like fingerprints: most everyone has them, yet each one is individual.

Not only that, but some knees are simply work better — or worse — than others. Sometimes it’s genetics, sometimes it’s an accident, sometimes it’s training, sometimes it’s a disease.

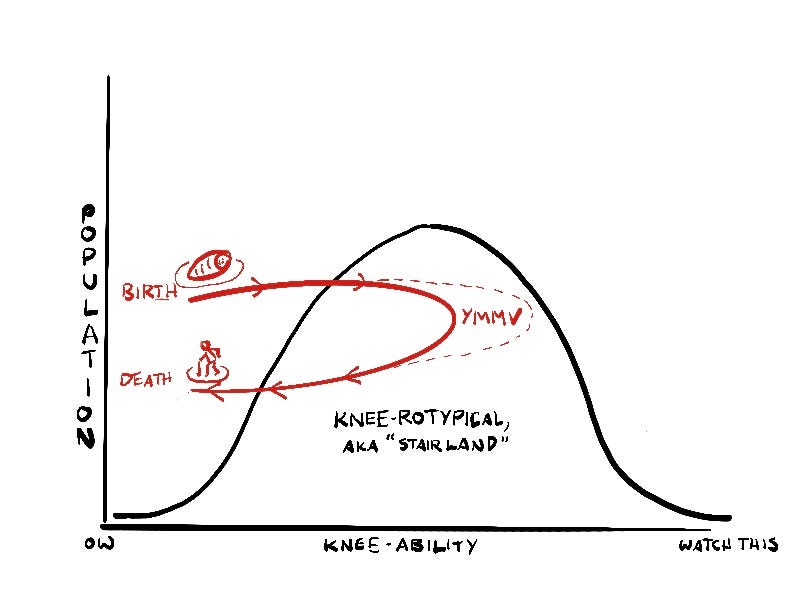

Think of it as a bell curve of how capable someone’s knees are:

Since most people fall into the middle of the bell curve — let’s call them, I don’t know, knee-rotypical — most of our traditions and architecture and expectations are built around a particular range of motion.

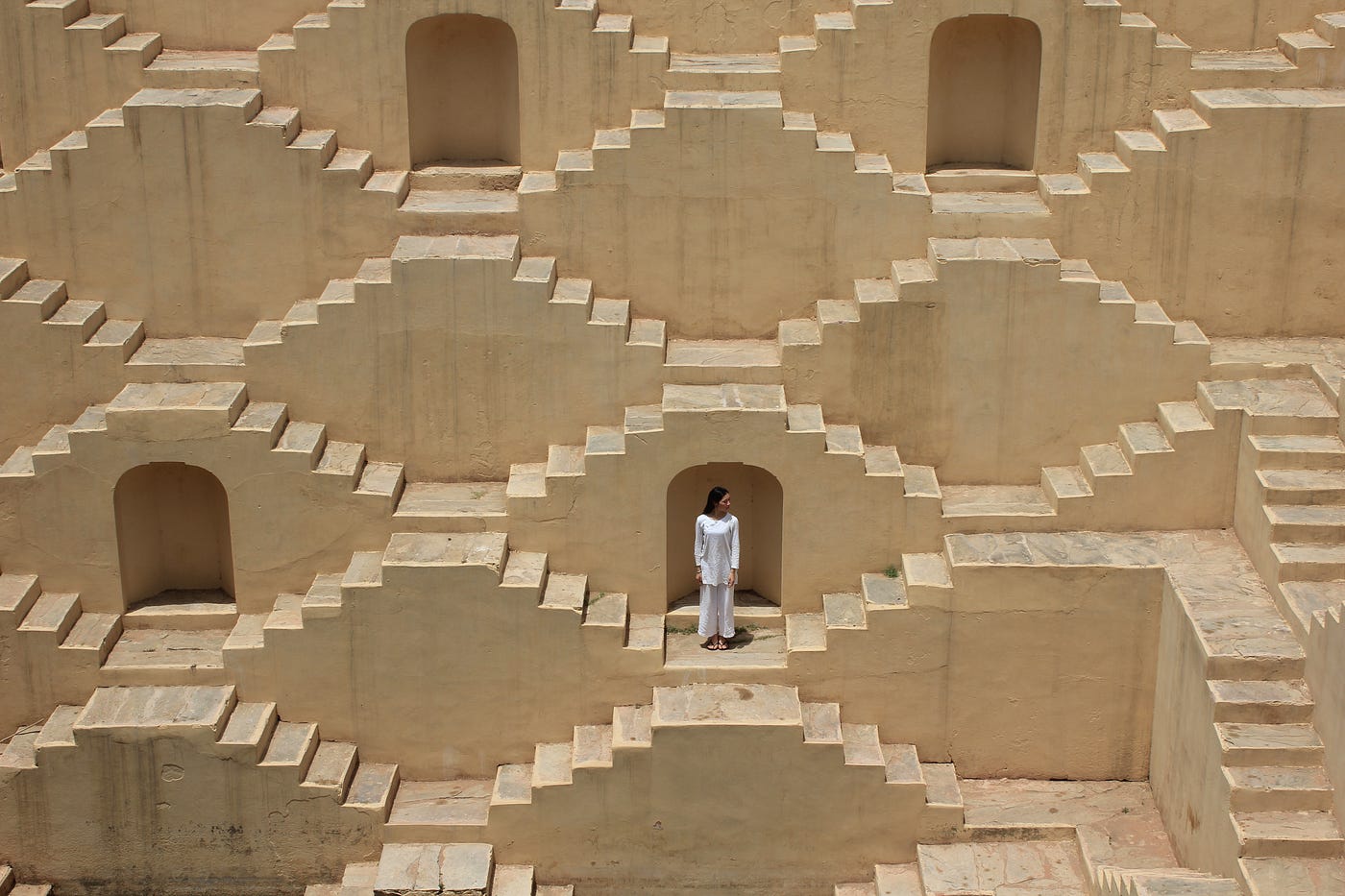

It’s easy to see all the places where knees are expected:

- stairs

- chairs

- cars

- line dancing

- pants (yes, I’m serious. Go ahead, try to put on your pants without bending your knees.)

That’s the world we live in, the world that we created over centuries. In the past, people with knees that fell on the less-capable side of the bell curve (knee-rodivergent, perhaps?) simply had to deal with it as best they could.

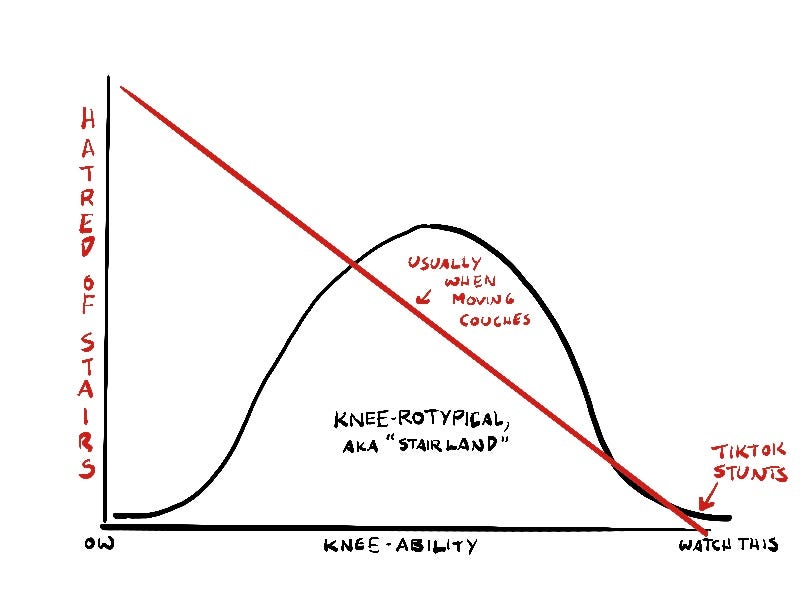

Of course, everybody had knee pain at some point or other. A sprain, a strain, a skinned knee, a bruise from a nighttime encounter with a coffee table. It happens to everyone.

The difference is, for some people, those injuries heal and the pain goes away. For others, it only ebbs and flows, and usually in the wrong direction. We even developed terms for it: chronic pain. Arthritis.

Eventually some parts of culture became civilized enough to invent things like elevators, ramps, wheelchairs, knee braces, and physical therapy that allowed people to participate in more of the world.

With a few putrescent exceptions, nobody would think less of a person with bad knees. They wouldn’t look at someone with a knee brace and tell them they were being lazy, or to just try harder.

I’d like to think that this happened because we realized the inherent value of every human being, regardless of their knee-ability, but in truth it probably had more to do with people realizing as they lived longer that they moved towards the left side of the bell curve, regardless of where they started.

In my case, I had pretty good knees through high school, enabling me to letter on the cross country and swim teams and also dance in the musicals and swing choir. My knees were great for that!

Then I joined the Marine Corps infantry, and it turned out that my knees were not so good at carrying heavy loads over long distances. Bilateral chondromalacia patella was the official term, and they thanked me for my honorable service and kicked me out.

That doesn’t mean that I had bad knees; it simply meant I didn’t have infantry knees. There’s a reason they’re known as the few, the proud; I lasted two years, and that’s longer than most people.

No one can take that away from me — but the injury did move me slightly along the bell curve. I found that I could still dance — but only certain kinds of dance that didn’t involve high impact. Ballet and jazz were cut off; my knees would give way after only a few grande jetes.

On the other hand, other dance forms, such as contact improv or kabuki, kept me low to the ground and relied more on leg strength than knees — so that’s what I did. I also took more elevators, bought a knee brace, and took up t’ai chi and biking (which strengthen the quadriceps and help keep my kneecap in line in spite of the decaying cartilage).

In short, I found systems that compensated for my knee-rodivergence — up to a point. Stairs weren’t a problem on warm days when I’d been sitting down most of the time, but if I’d gotten up at 4am to drive to Chicago to catch the first of three connecting flights with carry-on luggage and ended up at 10 pm on at the end of a long hike from a Manhattan subway station facing the four flights of stairs leading up to my friends apartment where I’d be sleeping, my knees were definitely a problem.

Um, hypothetically, of course. This is an analogy, after all. The point is, the world is made for knees. As people fall into the lower end of the bell curve, more and more accommodations are necessary to do more and more mundane things — up to the point where a knee is simply ripped out and replaced with a prosthetic, which (I’m told) usually works pretty well.

Almost all of us are going to go through this, as we get older. While we can put off the inevitable, it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when. There’s a reason my partner and I bought a house that is a single-story. There’s a reason I don’t run any more, and why my partner is more likely to sit cross-legged rather than kneeling in her meditation practice.

We accommodate. We find work-arounds. We use technology like knee braces and ibuprofen to compensate, so that we can better function in the world.

But we still hate stairs.

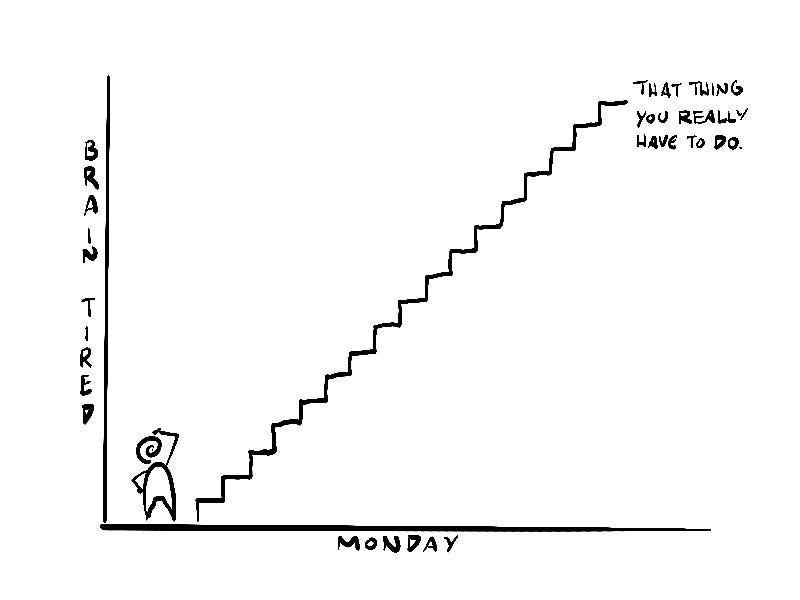

Imagine if it was brains instead of knees.

Here’s where we bring the analogy home.

Just like knees, the world we live in is built for a certain range of mental abilities. Our schools, our jobs, our entertainment and social events, they’re built to appeal to the way most — aka, typical — brains work.

They have developed over millennia based on the way most brains handle motivation, attention, and neat chemicals like dopamine.

Just like knees, there are a small-but-significant number of people (4.4% of adults, according to the NIH) whose brains don’t handle dopamine that way. Their neurotransmitters have developed differently — you might say, diverged — from the way most brains work.

Just like knees, there are ways to compensate — medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, notebooks, nootropics — that make it easier for the divergent to function in the typical world.

The rest of the time it’s a struggle.

Authorities like Dr. Russell Barkley call ADHD “the diabetes of the brain” but I think of it more like the arthritis in my knees:

- It’s not a visible disability

- It shows up in different ways, sometimes depending on how I’ve been taking care of myself and sometimes on my environment

- Some people have it worse than me, some better, and some (I can only imagine) don’t have pain in their knees at all.

- The symptoms are treatable with medication and lifestyle changes and “external scaffolding” (notebooks, apps, etc) but

- It’s not something that’s going to get any better.

It’s also something that I occasionally feel guilt and shame about. Something that I feel like I should be able to rise above. So what if your knee hurts? Get up those stairs! is just as familiar a refrain as Wow, you forgot about that conversation? What an idiot. Do better!

Of course, it’s not that I forgot anything. It’s much more frustrating than that. I remember things, just not when I need to.

The next time you wonder if neurodivergence exists, count the stairs.

And imagine if every single one was a struggle. That’s the world people with ADHD live in, work in, play in. It’s only a little less than 5% of us, so nobody’s asking you to change everything to suit us — but we appreciate if you’ll allow us a few accommodations, like moving around the meeting room or doodling in class meeting, or writing everything down — even the things you think it should be easy to remember.

We’re just figuring out how to get up those goddamn stairs.

*EMT-intermediate and a few kinesiology classes while earning my dance degree at best